Most people use slides when giving a presentation. Unfortunately, most slides are awful. Here are some tips to help.

This is a post I will re-visit each year. Here are the 2016 suggestions:

Do’s

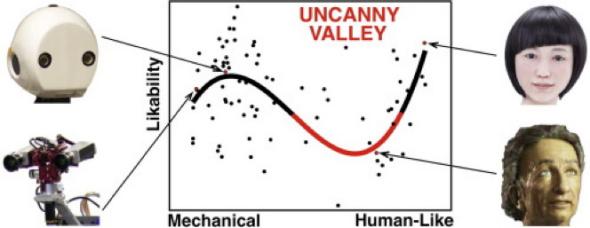

1. Use images and graphs. As much as can reasonably be allowed. Visuals trump words.

2. Make your slides readable. Use at most three font sizes. Large size is for titles/headlines, medium is for your main ideas, small is for supporting ideas. You may use bolding, but avoid italics and underlining as they are hard to read. Ensure contrast between the text and background.

3. Think about going to a blank slide when you want to talk and need the audience’s full attention. Most presentation clickers have a button that can do this. From the TED Talks book: “Just go to a blank, black slide and then the audience will get a vacation from images and pay more attention to your words. Then, when you go back to slides, they will be ready to go back to work.”

Don’ts

1. Don’t use slides made in LaTeX. LaTeX is great for making papers. But it makes boring presentations that look like paper subsets. Presentations aren’t for reading, they’re for listening and seeing. Every presentation I’ve seen where the slides were made in LaTeX Beamer has been boring. And, perhaps worse, each presentation is the same sort of boring, as there seems to be little customization. I’m sure it’s possible to give a good presentation with this tool, but I haven’t seen it.

2. Don’t create slides that work as a stand-alone document. You are there to give your presentation. If everything you want to say is already up on the slides, why are you there? Your job is not to make all-encompassing slides. It is to make slides that support your presentation.

3. Don’t put items on your slides that you don’t want to discuss. If the information is not important enough to mention, it shouldn’t be on your slides. Generally, slides shouldn’t speak for themselves. If you think someone might ask about it, move it to your backup slides.